Managerial Economics: Applications, Strategies and Tactics (MindTap Course List)

14th Edition

ISBN:9781305506381

Author:James R. McGuigan, R. Charles Moyer, Frederick H.deB. Harris

Publisher:James R. McGuigan, R. Charles Moyer, Frederick H.deB. Harris

Chapter3: Demand Analysis

Section: Chapter Questions

Problem 4E

Related questions

Question

I need help with question 2

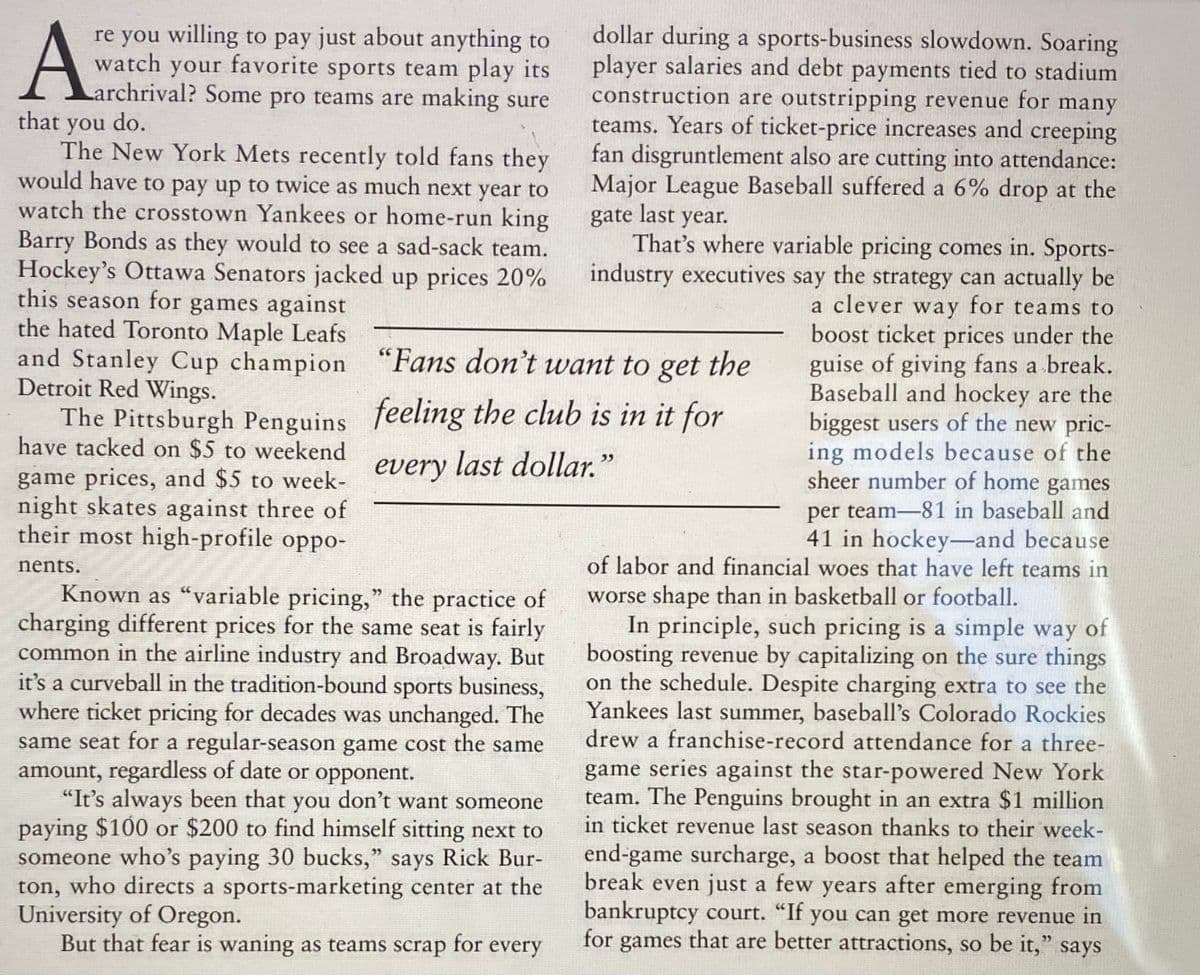

Transcribed Image Text:A

dollar during a sports-business slowdown. Soaring

player salaries and debt payments tied to stadium

construction are outstripping revenue for many

teams. Years of ticket-price increases and creeping

fan disgruntlement also are cutting into attendance:

Major League Baseball suffered a 6% drop at the

re you willing to pay just about anything to

watch your favorite sports team play its

Larchrival? Some pro teams are making sure

that you do.

The New York Mets recently told fans they

would have to pay up to twice as much next year to

watch the crosstown Yankees or home-run king

Barry Bonds as they would to see a sad-sack team.

Hockey's Ottawa Senators jacked up prices 20%

this season for games against

the hated Toronto Maple Leafs

and Stanley Cup champion “Fans don't want to get the

Detroit Red Wings.

gate last year.

That's where variable pricing comes in. Sports-

industry executives say the strategy can actually be

a clever way for teams to

boost ticket prices under the

guise of giving fans a break.

Baseball and hockey are the

biggest users of the new pric-

ing models because of the

sheer number of home games

The Pittsburgh Penguins feeling the club is in it for

have tacked on $5 to weekend

game prices, and $5 to week- every last dollar."

night skates against three of

their most high-profile oppo-

per team-81 in baseball and

41 in hockey-and because

of labor and financial woes that have left teams in

nents.

Known as “variable pricing," the practice of

charging different prices for the same seat is fairly

common in the airline industry and Broadway. But

it's a curveball in the tradition-bound sports business,

where ticket pricing for decades was unchanged. The

same seat for a regular-season game cost the same

amount, regardless of date or opponent.

"It's always been that

paying $100 or $200 to find himself sitting next to

someone who's paying 30 bucks," says Rick Bur-

ton, who directs a sports-marketing center at the

University of Oregon.

But that fear is waning as teams scrap for every

worse shape than in basketball or football.

In principle, such pricing is a simple way of

boosting revenue by capitalizing on the sure things

on the schedule. Despite charging extra to see the

Yankees last summer, baseball's Colorado Rockies

drew a franchise-record attendance for a three-

game series against the star-powered New York

team. The Penguins brought in an extra $1 million

in ticket revenue last season thanks to their week-

end-game surcharge, a boost that helped the team

break even just a few years after emerging from

bankruptcy court. "If you can get more revenue in

for games that

you

don't want someone

are better attractions, so be it," says

Transcribed Image Text:Tom Rooney, president of Team Lemieux, which

operates the Penguins.

The new plans carry some risk and complica-

tions. The plans require teams to gauge the quality

opponents months before the season starts, "and

that valuation can change very quickly," says Bernie

Mullin, a senior vice president at the NBA, which

has steered its teams away from the strategy. Indeed,

the Mets included the Philadelphia Phillies in their

“value plan"-but the Phillies soon afterward

became a better draw by signing slugger Jim Thome.

Assuming that fans will turn out for the best

games despite a price increase could be a mistake. In

November, the Ottawa Senators had nearly 2,500

empty seats for a game against the Montreal Cana-

diens, which carried a 10% surcharge; that game is

usually a sellout or close to it. The team also fell

short of a sellout a few weeks later against rival

Toronto, a matchup that usually draws a capacity

when marquee opponents come to town. Under the

Giants' tiered pricing plan, season-ticket holders pay

the lowest prices. Next in line are single-game tickets

to midweek games. And the priciest are single-game

tickets for Opening Day games, weekends and holi-

days. The price disparity among the packages range

from $1 per game for bleacher seats to more than

$20 per game for long-term box season tickets.

The Giants' main goal: Take advantage of fam

demand without drawing distinctions among oppo-

nents-or alienating season-ticket holders, who

account for more than two-thirds of sales. The plan

is "reinforced value for our season-ticket holders

of

that they have best pricing in ballpark," says Tom

McDonald, the Giants' senior vice president for

marketing.

Giants President Larry Baer says the plan net-

ted an additional $1 million in ticket revenue last

season, helping the heavily indebted club finish

with a slim profit of around $100,000. While Mr.

Baer says his team's plan has worked, he cautions

against pushing ticket discrepancies further. "Fans

don't want to get the feeling the club is in it for

every last dollar," he says.

crowd.

Senators fan Steven Duford says he skipped

both games because of the price increases. "“I do not

agree that I have to pay extra to see certain teams,"

he says. "I don't pay less for teams that usually

don't draw."

That sort of thinking has led some clubs, includ-

ing the San Francisco Giants, to avoid inflating prices

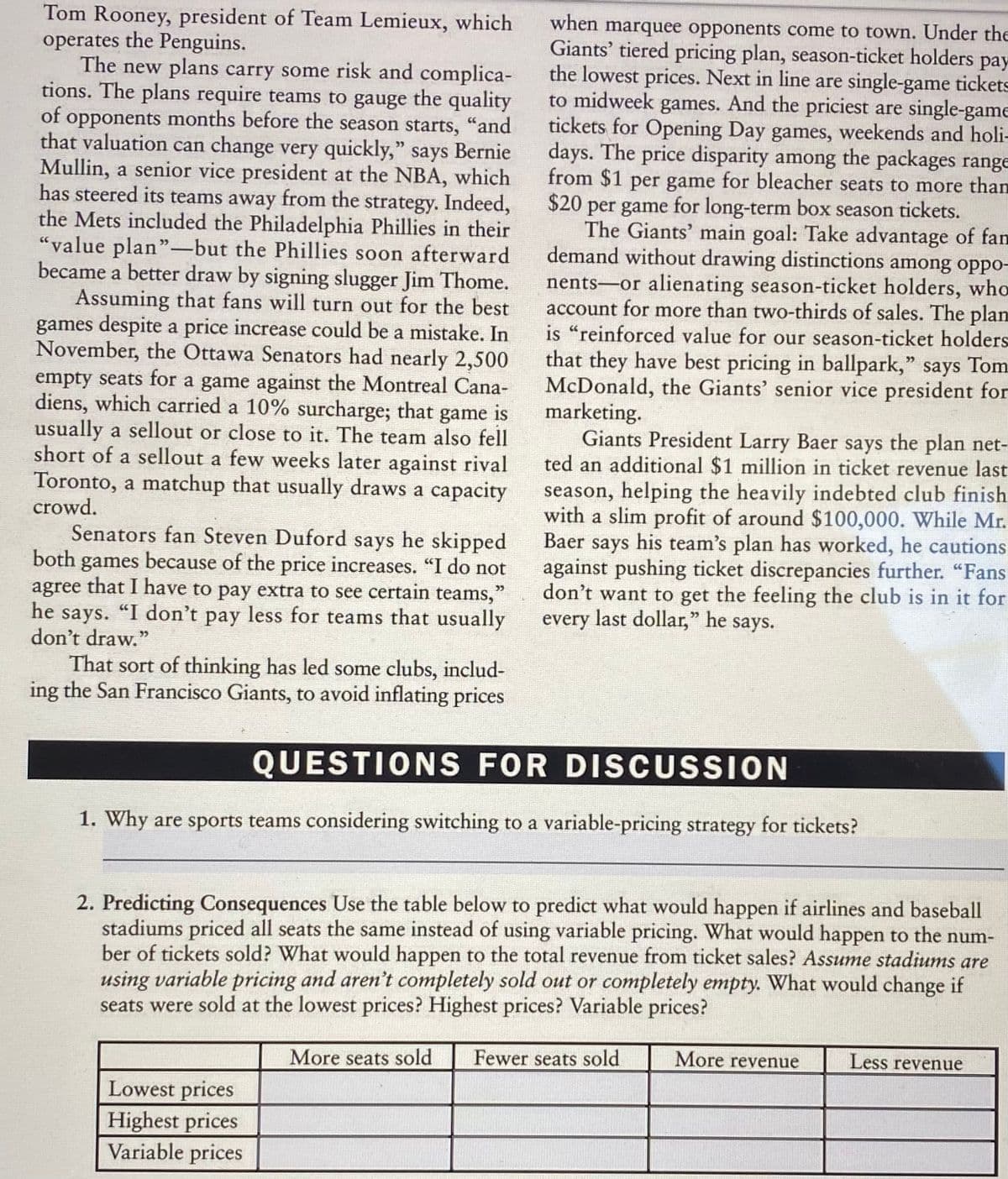

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. Why are sports teams considering switching to a variable-pricing strategy for tickets?

2. Predicting Consequences Use the table below to predict what would happen if airlines and baseball

stadiums priced all seats the same instead of using variable pricing. What would happen to the num-

ber of tickets sold? What would happen to the total revenue from ticket sales? Assume stadiums are

using variable pricing and aren't completely sold out or completely empty. What would change if

seats were sold at the lowest prices? Highest prices? Variable prices?

More seats sold

Fewer seats sold

More revenue

Less revenue

Lowest prices

Highest prices

Variable prices

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

Step by step

Solved in 3 steps with 2 images

Knowledge Booster

Learn more about

Need a deep-dive on the concept behind this application? Look no further. Learn more about this topic, economics and related others by exploring similar questions and additional content below.Recommended textbooks for you

Managerial Economics: Applications, Strategies an…

Economics

ISBN:

9781305506381

Author:

James R. McGuigan, R. Charles Moyer, Frederick H.deB. Harris

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Principles of Economics 2e

Economics

ISBN:

9781947172364

Author:

Steven A. Greenlaw; David Shapiro

Publisher:

OpenStax

Managerial Economics: Applications, Strategies an…

Economics

ISBN:

9781305506381

Author:

James R. McGuigan, R. Charles Moyer, Frederick H.deB. Harris

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Principles of Economics 2e

Economics

ISBN:

9781947172364

Author:

Steven A. Greenlaw; David Shapiro

Publisher:

OpenStax