Explain what the procedure is, what are the independent and dependent variables ? What experimental research did they use

Explain what the procedure is, what are the independent and dependent variables ? What experimental research did they use

Ciccarelli: Psychology_5 (5th Edition)

5th Edition

ISBN:9780134477961

Author:Saundra K. Ciccarelli, J. Noland White

Publisher:Saundra K. Ciccarelli, J. Noland White

Chapter1: The Science Of Psychology

Section: Chapter Questions

Problem 1TY

Related questions

Question

Explain what the procedure is, what are the independent and dependent variables ? What experimental research did they use ?

Transcribed Image Text:10:40

control or regulate their naturally occurring thoughts

and feelings (cf. Shafir et al., 2018). Following this part,

Neural Self-Regulation of Social-Media Temptations

1 Mental Logout- Be...

1532

200 ms

+

G

Distraction

+

250 ms

Event-related potential (ERP)

recording and analysis

Dashboard

et al., 2018). The average percentage of correct responses

was very high (91.66 %, SE 4.65%). Second, during

breaks between experimental blocks, the experimenter

asked participants to give examples of how they imple-

mented the instructions in the two conditions and cor-

rected them as needed. Third, during the experiment,

we videotaped and watched participants' faces to make

sure they were concentrating on the task. Finally, at

the completion of the experimental trials, eight addi-

tional trials (four for each of the two instructions) were

followed by a screen that asked participants to write

down how they implemented the required instruction.

A judge who was blind to participants' instructions.

coded each sentence as attentional distraction or temp-

tation. The level of accuracy was very high (96.5%),

indicative of adequate implementation of the instruc-

tions (for more information, see Table $1 in the Supple-

mental Material).

Time to Blink

700 ms

EEGS were recorded using an Active Two EEG recording

system (Biosemi, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Data

200 ms

Time

exceeding 100 µV from CDA electrodes (P7, P8, Po7,

Po8, Po3, and Po4). Following LPP analysis conventions

(e.g., Shafir et al., 2018), we excluded from the aver-

aged ERP waveforms any activity exceeding 80 µV from

oool

Calendar

D

were followed by a screen asking participants to report

which instruction they had just implemented (Shafir

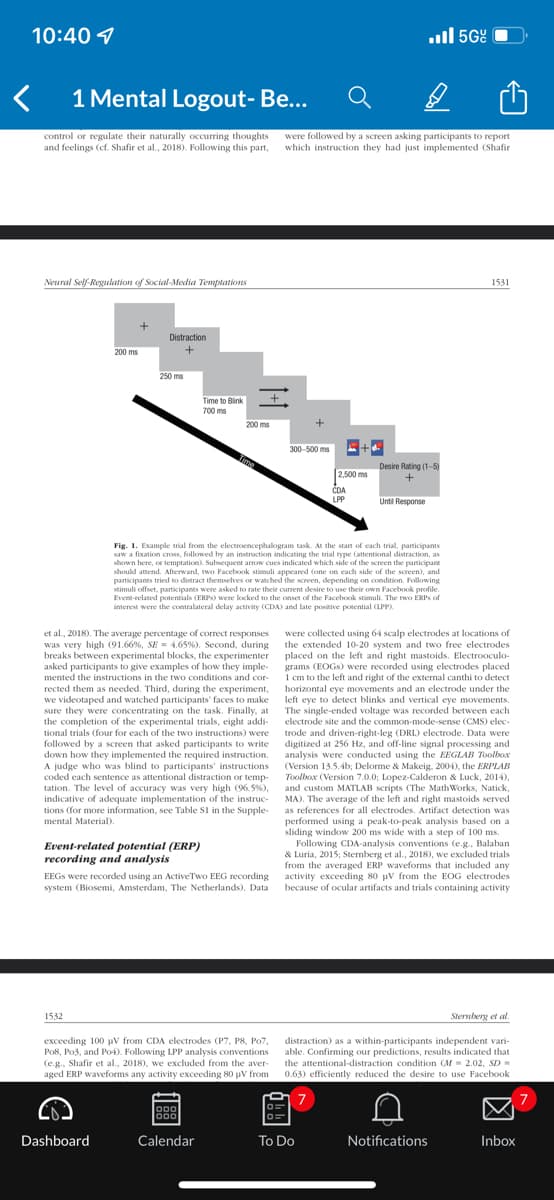

Fig. 1. Example trial from the electroencephalogram task. At the start of each trial, participants

saw a fixation cross, followed by an instruction indicating the trial type (attentional distraction, as

shown here, or temptation). Subsequent arrow cues indicated which side of the screen the participant

should attend. Afterward, two Facebook stimuli appeared (one on each side of the screen), and

participants tried to distract themselves or watched the screen, depending on condition. Following

stimuli offset, participants were asked to rate their current desire to use their own Facebook profile.

Event-related potentials (ERPs) were locked to the onset of the Facebook stimuli. The two ERPs of

interest were the contralateral delay activity (CDA) and late positive potential (LPP).

300-500 ms

2,500 ms

CDA

LPP

..5Gº

Desire Rating (1-5)

+

Until Response

To Do

were collected using 6-4 scalp electrodes at locations of

the extended 10-20 system and two free electrodes

placed on the left and right mastoids. Electrooculo-

grams (EOGs) were recorded using electrodes placed

1 cm to the left and right of the external canthi to detect

horizontal eye movements and an electrode under the

left eye to detect blinks and vertical eye movements.

The single-ended voltage was recorded between each

electrode site and the common-mode-sense (CMS) elec-

trode and driven-right-leg (DRL) electrode. Data were

digitized at 256 Hz, and off-line signal processing and

analysis were conducted using the EEGLAB Toolbox

(Version 13.5.4b; Delorme & Makeig, 2004), the ERPLAB

Toolbox (Version 7.0.0; Lopez-Calderon & Luck, 2014),

and custom MATLAB scripts (The MathWorks, Natick,

MA). The average of the left and right mastoids served

as references for all electrodes. Artifact detection was

performed using a peak-to-peak analysis based on a

sliding window 200 ms wide with a step of 100 ms.

1531

Following CDA-analysis conventions (e.g., Balaban

& Luria, 2015; Sternberg et al., 2018), we excluded trials

from the averaged ERP waveforms that included any

activity exceeding 80 µV from the EOG electrodes

because of ocular artifacts and trials containing activity

Notifications

distraction) as a within-participants independent vari-

able. Confirming our predictions, results indicated that

the attentional-distraction condition (M 2.02, SD =

0.63) efficiently reduced the desire to use Facebook

7

Sternberg et al.

Inbox

7

Transcribed Image Text:10:40

sures used in the study (additional background informa-

tion collected for pilot purposes is described in the

Supplemental Material available online). All experimen-

tal procedures were approved by the institutional

review board of Tel Aviv University and were performed

in accordance with the approved guidelines.

1530

1 Mental Logout- Be...

changing their Facebook password (cf. Sternberg et al.,

2018, 2020). This procedure was followed to enhance

the value and saliency of Facebook stimuli, and it guar-

anteed that participants would not use Facebook imme-

diately prior to or immediately following the main EEG

experiment. In general, deprivation procedures are

well-es

Il-established in animal and human studies across

many fields (e.g., Grimm et al., 2001), including Face-

book usage (Sternberg et al., 2018, 2020). Importantly,

Sternberg et al. (2018) showed that this deprivation

procedure does not bias naturally occurring social-

network usage, as revealed by finding a significant

medium-size positive correlation between deprived

Facebook usage time in the laboratory and nondeprived

Facebook usage time at home.

In the main experiment, following EEG setup, we

explained to participants that during the task, they

would view well-recognized social-media-related images

under two conditions: (a) a temptation condition that

involved naturally watching social-media stimuli and

allowing social-media-related thoughts and associated

intentions to use social-media (e.g., freely thinking

about one's Facebook profile, recent activities, and con-

tent) and (b) an attentional-distraction condition that

involved trying to control the influence of social-media

stimuli and associated thoughts by directing attention

to absorbing neutral thoughts unrelated to Facebook

stimuli (i.e., thinking about geometric shapes or daily

routine activities). The instructions for both conditions

are considered the gold standard in self-regulation

research; multiple prior studies show the efficacy of

similar attentional-distraction manipulations in regulat-

ing unpleasant emotions and appetitive desires (Shafir

et al., 2018; for a review, see Sheppes, 2020).

The experimenter taught the participants how to

implement the instructions in both conditions (giving

two examples for each condition). Then, during a four-

trial learning phase, participants were asked to talk out

loud about how they implemented each instruction.

(two examples for each instruction), and they were

corrected by the experimenter whenever they imple-

mented the instructions in either condition incorrectly.

Specifically, in the attentional-distraction condition,

participants were corrected by the experimenter if their

produced thoughts were not perceived as neutral for

them, if these thoughts were somehow related to Face-

book stimuli, or if these thoughts did not fit one of the

two categories (geometric shapes or daily routine activi-

ties). In the temptation condition, participants were

corrected if their thoughts and feelings were not related

to their personal Facebook usage or if they tried to

control or regulate their naturally occurring thoughts

and feelings (cf. Shafir et al., 2018). Following this part,

Neural Self-Regulation of Social-Media Temptations

G

Dashboard

188

Calendar

distance of approximately 70 cm.

Procedure

Twenty-four hours prior to the experiment, we deacti-

vated participants' access to Facebook for 48 hr by

B

Sternberg et al.

we explained to participants the general structure of

each trial, followed by a 20-trial practice phase.

..5Gº

The actual task consisted of 16 blocks that were

separated by short breaks; each block contained 25

trials (yielding a total of 400 analyzed trials). Each trial

(see Fig. 1) started with a fixation cross in the middle

of the screen, followed by a screen containing the

required instruction ("Distraction" for the attentional-

distraction condition or "Watch" for the temptation con-

dition). Then arrow cues pointing right or left (with an

equal probability) indicated which side of the screen

the participant should attend. This screen was followed

by the presentation of two Facebook stimuli (randomly

selected with equal probability to appear in each of the

two experimental conditions), one on each side of the

screen. The bilateral presentation of Facebook stimuli

is required for CDA analysis (see CDA Analysis section

below; for a review, see Luria et al., 2016). During the

presentation of Facebook stimuli, participants imple-

mented the required instruction ("watch" social-media

content or "distract" oneself from social-media content).

Following stimuli offset, participants were asked to rate

their current desire to use their own Facebook profile

on a scale ranging from 1 (not feeling a desire at all) to

5 (feeling extreme desire).

Following standard procedures in CDA experiments

that are intended to minimize perceptual differences.

(e.g., Balaban & Luria, 2015; Luria et al., 2016), we

instructed participants to maintain their gaze at the

center of the screen during the presentation of Face-

book stimuli. Trials that included eye movements were

excluded from analyses. Participants were taught to

blink in two defined points prior to and following stim-

uli presentation.

Importantly, the fact that both experimental condi-

tions used the same stimuli and that trials with eye

movements were excluded preclude low-level percep-

tual alternative interpretations for the observed differ-

ences between the temptation and attentional-distraction

conditions. Specifically, by excluding trials with eye

movements, we ruled out the possibility that people

used attentional-deployment strategies that entailed

bottom-up processes (e.g., closing their eyes or divert-

ing their gaze) rather than the instructed top-down

processes (e.g., thinking about shapes or daily neutral

activities while maintaining their gaze at the center) to

regulate their emotions (for a discussion, see van Reekum

et al., 2007).

To Do

Several measures were used to ensure that partici-

pants concentrated during the task and correctly fol-

lowed instructions. First, 60 randomly chosen trials

were followed by a screen asking participants to report

which instruction they had just implemented (Shafir

7

C

Notifications

1531

Inbox

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

This is a popular solution!

Trending now

This is a popular solution!

Step by step

Solved in 3 steps

Recommended textbooks for you

Ciccarelli: Psychology_5 (5th Edition)

Psychology

ISBN:

9780134477961

Author:

Saundra K. Ciccarelli, J. Noland White

Publisher:

PEARSON

Cognitive Psychology

Psychology

ISBN:

9781337408271

Author:

Goldstein, E. Bruce.

Publisher:

Cengage Learning,

Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and …

Psychology

ISBN:

9781337565691

Author:

Dennis Coon, John O. Mitterer, Tanya S. Martini

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Ciccarelli: Psychology_5 (5th Edition)

Psychology

ISBN:

9780134477961

Author:

Saundra K. Ciccarelli, J. Noland White

Publisher:

PEARSON

Cognitive Psychology

Psychology

ISBN:

9781337408271

Author:

Goldstein, E. Bruce.

Publisher:

Cengage Learning,

Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and …

Psychology

ISBN:

9781337565691

Author:

Dennis Coon, John O. Mitterer, Tanya S. Martini

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Psychology in Your Life (Second Edition)

Psychology

ISBN:

9780393265156

Author:

Sarah Grison, Michael Gazzaniga

Publisher:

W. W. Norton & Company

Cognitive Psychology: Connecting Mind, Research a…

Psychology

ISBN:

9781285763880

Author:

E. Bruce Goldstein

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Theories of Personality (MindTap Course List)

Psychology

ISBN:

9781305652958

Author:

Duane P. Schultz, Sydney Ellen Schultz

Publisher:

Cengage Learning