Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (MindTap Course List)

14th Edition

ISBN:9781305073951

Author:Cecie Starr, Ralph Taggart, Christine Evers, Lisa Starr

Publisher:Cecie Starr, Ralph Taggart, Christine Evers, Lisa Starr

Chapter33: Sensory Perception

Section: Chapter Questions

Problem 1CT: Like other nocturnal carnivores, the ferret shown in FIGURE 33.13 has light-reflecting material in...

Related questions

Question

Using DIRECT evidence from the text, provide a biological explanation for why pest companies should limit the production of sugary baits in order to control cockroaches.

USE THE TERMS: behavioral resistance, glucose, taste buds

THIS IS NOT ESSAY OR WRITING HELP!!

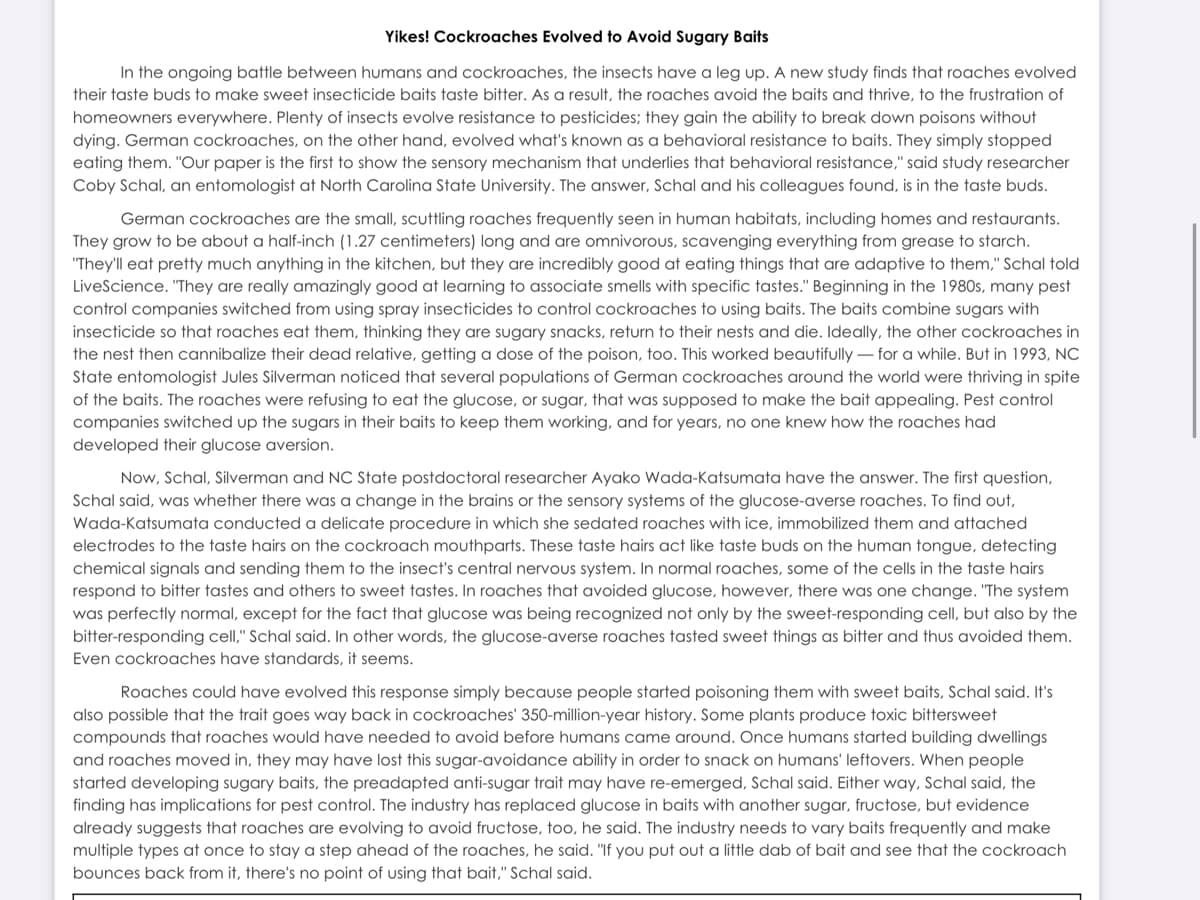

Transcribed Image Text:Yikes! Cockroaches Evolved to Avoid Sugary Baits

In the ongoing battle between humans and cockroaches, the insects have a leg up. A new study finds that roaches evolved

their taste buds to make sweet insecticide baits taste bitter. As a result, the roaches avoid the baits and thrive, to the frustration of

homeowners everywhere. Plenty of insects evolve resistance to pesticides; they gain the ability to break down poisons without

dying. German cockroaches, on the other hand, evolved what's known as a behavioral resistance to baits. They simply stopped

eating them. "Our paper is the first to show the sensory mechanism that underlies that behavioral resistance," said study researcher

Coby Schal, an entomologist at North Carolina State University. The answer, Schal and his colleagues found, is in the taste buds.

German cockroaches are the small, scuttling roaches frequently seen in human habitats, including homes and restaurants.

They grow to be about a half-inch (1.27 centimeters) long and are omnivorous, scavenging everything from grease to starch.

"They'll eat pretty much anything in the kitchen, but they are incredibly good at eating things that are adaptive to them," Schal told

LiveScience. "They are really amazingly good at learning to associate smells with specific tastes." Beginning in the 1980s, many pest

control companies switched from using spray insecticides to control cockroaches to using baits. The baits combine sugars with

insecticide so that roaches eat them, thinking they are sugary snacks, return to their nests and die. Ideally, the other cockroaches in

the nest then cannibalize their dead relative, getting a dose of the poison, too. This worked beautifully – for a while. But in 1993, NC

State entomologist Jules Silverman noticed that several populations of German cockroaches around the world were thriving in spite

of the baits. The roaches were refusing to eat the glucose, or sugar, that was supposed to make the bait appealing. Pest control

companies switched up the sugars in their baits to keep them working, and for years, no one knew how the roaches had

developed their glucose aversion.

Now, Schal, Silverman and NC State postdoctoral researcher Ayako Wada-Katsumata have the answer. The first question,

Schal said, was whether there was a change in the brains or the sensory systems of the glucose-averse roaches. To find out,

Wada-Katsumata conducted a delicate procedure in which she sedated roaches with ice, immobilized them and attached

electrodes to the taste hairs on the cockroach mouthparts. These taste hairs act like taste buds on the human tongue, detecting

chemical signals and sending them to the insect's central nervous system. In normal roaches, some of the cells in the taste hairs

respond to bitter tastes and others to sweet tastes. In roaches that avoided glucose, however, there was one change. "The system

was perfectly normal, except for the fact that glucose was being recognized not only by the sweet-responding cell, but also by the

bitter-responding cell," Schal said. In other words, the glucose-averse roaches tasted sweet things as bitter and thus avoided them.

Even cockroaches have standards, it seems.

Roaches could have evolved this response simply because people started poisoning them with sweet baits, Schal said. It's

also possible that the trait goes way back in cockroaches' 350-million-year history. Some plants produce toxic bittersweet

compounds that roaches would have needed to avoid before humans came around. Once humans started building dwellings

and roaches moved in, they may have lost this sugar-avoidance ability in order to snack on humans' leftovers. When people

started developing sugary baits, the preadapted anti-sugar trait may have re-emerged, Schal said. Either way, Schal said, the

finding has implications for pest control. The industry has replaced glucose in baits with another sugar, fructose, but evidence

already suggests that roaches are evolving to avoid fructose, too, he said. The industry needs to vary baits frequently and make

multiple types at once to stay a step ahead of the roaches, he said. "If you put out a little dab of bait and see that the cockroach

bounces back from it, there's no point of using that bait," Schal said.

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

This is a popular solution!

Trending now

This is a popular solution!

Step by step

Solved in 2 steps

Knowledge Booster

Learn more about

Need a deep-dive on the concept behind this application? Look no further. Learn more about this topic, biology and related others by exploring similar questions and additional content below.Recommended textbooks for you

Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (MindTap…

Biology

ISBN:

9781305073951

Author:

Cecie Starr, Ralph Taggart, Christine Evers, Lisa Starr

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (MindTap…

Biology

ISBN:

9781337408332

Author:

Cecie Starr, Ralph Taggart, Christine Evers, Lisa Starr

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Biology (MindTap Course List)

Biology

ISBN:

9781337392938

Author:

Eldra Solomon, Charles Martin, Diana W. Martin, Linda R. Berg

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (MindTap…

Biology

ISBN:

9781305073951

Author:

Cecie Starr, Ralph Taggart, Christine Evers, Lisa Starr

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Biology: The Unity and Diversity of Life (MindTap…

Biology

ISBN:

9781337408332

Author:

Cecie Starr, Ralph Taggart, Christine Evers, Lisa Starr

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Biology (MindTap Course List)

Biology

ISBN:

9781337392938

Author:

Eldra Solomon, Charles Martin, Diana W. Martin, Linda R. Berg

Publisher:

Cengage Learning