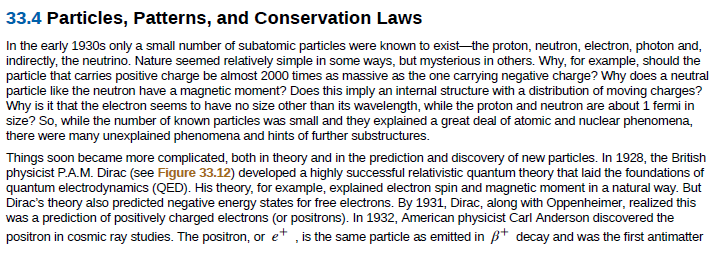

33.4 Particles, Patterns, and Conservation Laws In the early 1930s only a small number of subatomic particles were known to exist-the proton, neutron, electron, photon and, indirectly, the neutrino. Nature seemed relatively simple in some ways, but mysterious in others. Why, for example, should the particle like the neutron have a magnetic moment? Does this imply an internal structure with a distribution of moving charges? Why is it that the electron seems to have no size other than its wavelength, while the proton and neutron are about 1 fermi in size? So, while the number of known particles was small and they explained a great deal of atomic and nuclear phenomena, there were many unexplained phenomena and hints of further substructures. Things soon became more complicated, both in theory and in the prediction and discovery of new particles. In 1928, the British physicist P.A.M. Dirac (see Figure 33.12) developed a highly successful relativistic quantum theory that laid the foundations of quantum electrodynamics (QED). His theory, for example, explained electron spin and magnetic moment in a natural way. But Dirac's theory also predicted negative energy states for free electrons. By 1931, Dirac, along with Oppenheimer, realized this was a prediction of positively charged electrons (or positrons). In 1932, American physicist Carl Anderson discovered the positron in cosmic ray studies. The positron, or e+ , is the same particle as emitted in B+ decay and was the first antimatter that was discovered. In 1935, Yukawa predicted pions as the carriers of the strong nuclear force, and they were eventually discovered. Muons were discovered in cosmic ray experiments in 1937, and they seemed to be heavy, unstable versions of electrons and positrons. After World War II, accelerators energetic enough to create these particles were built. Not only were predicted and known particles created, but many unexpected particles were observed. Initially called elementary particles, their numbers proliferated to dozens and then hundreds, and the term "particle zoo" became the physicist's lament at the lack of simplicity. But patterns were observed in the particle zoo that led to simplifying ideas such as quarks, as we shall soon see. Figure 33.12 P.A.M. Dirac's theory of relativistic quantum mechanics not only explained a great deal of what was known, it also predicted antimatter. (credit: Cambridge University, Cavendish Laboratory)

33.4 Particles, Patterns, and Conservation Laws In the early 1930s only a small number of subatomic particles were known to exist-the proton, neutron, electron, photon and, indirectly, the neutrino. Nature seemed relatively simple in some ways, but mysterious in others. Why, for example, should the particle like the neutron have a magnetic moment? Does this imply an internal structure with a distribution of moving charges? Why is it that the electron seems to have no size other than its wavelength, while the proton and neutron are about 1 fermi in size? So, while the number of known particles was small and they explained a great deal of atomic and nuclear phenomena, there were many unexplained phenomena and hints of further substructures. Things soon became more complicated, both in theory and in the prediction and discovery of new particles. In 1928, the British physicist P.A.M. Dirac (see Figure 33.12) developed a highly successful relativistic quantum theory that laid the foundations of quantum electrodynamics (QED). His theory, for example, explained electron spin and magnetic moment in a natural way. But Dirac's theory also predicted negative energy states for free electrons. By 1931, Dirac, along with Oppenheimer, realized this was a prediction of positively charged electrons (or positrons). In 1932, American physicist Carl Anderson discovered the positron in cosmic ray studies. The positron, or e+ , is the same particle as emitted in B+ decay and was the first antimatter that was discovered. In 1935, Yukawa predicted pions as the carriers of the strong nuclear force, and they were eventually discovered. Muons were discovered in cosmic ray experiments in 1937, and they seemed to be heavy, unstable versions of electrons and positrons. After World War II, accelerators energetic enough to create these particles were built. Not only were predicted and known particles created, but many unexpected particles were observed. Initially called elementary particles, their numbers proliferated to dozens and then hundreds, and the term "particle zoo" became the physicist's lament at the lack of simplicity. But patterns were observed in the particle zoo that led to simplifying ideas such as quarks, as we shall soon see. Figure 33.12 P.A.M. Dirac's theory of relativistic quantum mechanics not only explained a great deal of what was known, it also predicted antimatter. (credit: Cambridge University, Cavendish Laboratory)

Related questions

Question

Particles, Patterns, and Conservation Laws

• Define matter and antimatter.

• Outline the differences between hadrons and leptons.

• State the differences between mesons and baryons.

Transcribed Image Text:33.4 Particles, Patterns, and Conservation Laws

In the early 1930s only a small number of subatomic particles were known to exist-the proton, neutron, electron, photon and,

indirectly, the neutrino. Nature seemed relatively simple in some ways, but mysterious in others. Why, for example, should the

particle like the neutron have a magnetic moment? Does this imply an internal structure with a distribution of moving charges?

Why is it that the electron seems to have no size other than its wavelength, while the proton and neutron are about 1 fermi in

size? So, while the number of known particles was small and they explained a great deal of atomic and nuclear phenomena,

there were many unexplained phenomena and hints of further substructures.

Things soon became more complicated, both in theory and in the prediction and discovery of new particles. In 1928, the British

physicist P.A.M. Dirac (see Figure 33.12) developed a highly successful relativistic quantum theory that laid the foundations of

quantum electrodynamics (QED). His theory, for example, explained electron spin and magnetic moment in a natural way. But

Dirac's theory also predicted negative energy states for free electrons. By 1931, Dirac, along with Oppenheimer, realized this

was a prediction of positively charged electrons (or positrons). In 1932, American physicist Carl Anderson discovered the

positron in cosmic ray studies. The positron, or e+ , is the same particle as emitted in B+ decay and was the first antimatter

Transcribed Image Text:that was discovered. In 1935, Yukawa predicted pions as the carriers of the strong nuclear force, and they were eventually

discovered. Muons were discovered in cosmic ray experiments in 1937, and they seemed to be heavy, unstable versions of

electrons and positrons. After World War II, accelerators energetic enough to create these particles were built. Not only were

predicted and known particles created, but many unexpected particles were observed. Initially called elementary particles, their

numbers proliferated to dozens and then hundreds, and the term "particle zoo" became the physicist's lament at the lack of

simplicity. But patterns were observed in the particle zoo that led to simplifying ideas such as quarks, as we shall soon see.

Figure 33.12 P.A.M. Dirac's theory of relativistic quantum mechanics not only explained a great deal of what was known, it also predicted antimatter.

(credit: Cambridge University, Cavendish Laboratory)

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

Step by step

Solved in 2 steps