Principles Of Marketing

17th Edition

ISBN:9780134492513

Author:Kotler, Philip, Armstrong, Gary (gary M.)

Publisher:Kotler, Philip, Armstrong, Gary (gary M.)

Chapter1: Marketing: Creating Customer Value And Engagement

Section: Chapter Questions

Problem 1.1DQ

Related questions

Question

Mention at least 5 specif points from this article ?

Transcribed Image Text:-1-prod-fleet01-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com/blackboard.learn.xythos.prod/58249d599753b/1138605?X-Blackboa... Q

1 / 17 1

JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC MARKETING 14 353-368 (DECEMBER 2006)

67% + | @ »

Routledge

Taver & Sanck Croup

Identifying fair trade in consumption choice

JOHN CONNOLLY*

Dublin City University Business School, Dublin City University, Collins Avenue, Dublin 9,

Ireland

DEIRDRE SHAW

School of Business and Management, University of Glasgow, West Quadrangle, Gilbert Scott

Building, Glasgow, G12 8QQ, UK

Although increased consumer concern for ethical issues has been recognised in

research, this has tended to explore such concerns in isolation, neglecting to consider

the often complex interaction between ethical issues in consumer decision-making.

Such interrelationships are important to the study of fair trade in terms of providing a

richer understanding of market potential and development in strategic decision-

making. The present paper, therefore, seeks to explore fair trade within the context of

other discursive narratives such as green consuming, ethical consuming, and voluntary

simplicity and the strategic marketing implications for fair trade organisations.

KEYWORDS: Fair trade; green consumer; ethical consumer; voluntary simplicity; brands

INTRODUCTION

Interest in the issues surrounding fair trade have gained increasing prominence in both the

marketplace and within the marketing literature (e.g. Doonar, 2004a,b; McDonagh, 2002; Shaw

et al., 2000). While some research has explored consumer responses to fair trade this has tended to

explore fair trade in isolation (e.g. Shaw et al., 2000; Strong, 1997). Despite the fact that the

discursive claims of green consumption, ethical consumption, and voluntary simplicity are often

positioned separately within the literature (e.g. Craig-Lees and Hill, 2002; Laroche et al., 2001;

Peatttie, 2001) or alternatively, as complimentary activities (e.g. Robins and Roberts, 1997), the

issue of fair trade within these narratives has not been subject to much scrutiny. The purpose of

this paper is to review the existing published research on fair trade alongside other ethical

consumer concerns such as ethical consumption, green consumption and voluntary simplicity.

The exploration of such interconnections is important, as research exploring fair trade in isolation

may fail to uncover the often complex interaction between all issues of concern to the consumer.

Following on from this, we outline three areas within the realm of marketing and strategy where

fair trade organisations can engage with consumers on a broad ranging and inclusive level, to take

* Corresponding author: john.connolly@dit.ie

Journal of Strategic Marketing ISSN 0965-254X print/ISSN 1466-4488 online ©2006 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/09652540600960675

354

Q ✩ I

BACKGROUND

ROUNDI

The fair trade market

CONNOLLY AND SHAW

account of the diverse issues that concern consumers of fair trade products. Finally, the resultant

implications of this wider perspective for strategic decision-making in organisations will be

discussed.

Sales of fair trade products doubled between 2001 and 2003 (Fairtrade Foundation, 2003),¹

resulting in current annual sales of just over €147m in the UK. In Europe sales have now topped

€560m. Indeed, the most recent literature on the subject refers to the significant growth in fair

trade (Doonar, 2004a,b; Jones et al., 2003).

Moreover, the growth in the market for fair trade products cannot be dismissed as anecdotal.

Indeed, it is important to note the wider context within which this growth is placed. Other

products reflective of consumer ethical or moral concerns have also experienced significant

growth rates, for instance, in the UK consumer demand in the organic food sector rose by 55%

between the years 2000 and 2001 (Desai, 2001). Meanwhile Europe has also seen a boom in the

organic food market (Soil Association, 2006). Further examples of consumer ethical concern can

be found in financial services offering an ethical focus, as well as consumers' willingness to boycott

companies-recent examples of which include Coca-Cola, Esso, Nestlé and Shell. It is important

to note, however, that although fair trade has been experiencing significant growth rates, fair

trade tea and coffee together only capture 2.3% of the market (Williams and Doane, 2002).

Indeed, fair trade only represents about 0.01% of all goods traded globally (Fairtrade Foundation,

2004).

Fair trade labelling organisations in particular have played a key role in the development of the

fair trade market, creating what Renard (2003) refers to as a reality within the market instead of

constructing an alternative outside the market. Playing an important role in the growth of fair

trade in the UK was the introduction of Cafedirect, a fair trade coffee brand, to mainstream retail

outlets. In recognising the importance of traditional product features, including quality and taste,

Cafedirect sought to be more than just an ethical brand and also placed importance on product

quality and availability in mainstream markets. The label also enjoys widespread recognition in

Europe.

The increased presence of fair trade products, including coffee, tea, honey, bananas, orange

juice and chocolate, in mainstream as well as alternative outlets has improved access, range and

availability of these products. This growth, however, has not been reflected in all markets. Unlike

the food sector where fair trade products can be readily identified by a label, such developments

have been slow in other areas, including clothing, homewares and flowers, where availability

tends to be restricted to specialised outlets. This is reflected in markets in the UK and elsewhere.

Yet there appears to be a growing awareness among consumers of the environmental and social

impact of their consumption particularly in response to a globalised economy (Giddens, 1991,

1994). This perspective is important in light of research that has revealed that interconnections

exist between different consumer ethical concerns (Shaw and Clarke 1999; Shaw et al., 2000). As

a result, a danger exists in examining fair trade in isolation, as it is likely that this concern exists

alongside a number of issues of concern to the consumer, such as environmental or animal welfare

issues. In addition, recent developments in the market may further add to consumer confusion

such as the development of own-brand fair trade products by supermarkets such as Tesco and

±

Transcribed Image Text:X

Bb untitled

t-1-prod-fleet01-xythos.content.blackboardcdn

CONSUMPTION CHOICE

Environmentally concerned consumers

Environmentally/ecologically

conscious consumers

Green consumers

X

3 / 17 |.

Copy

Sainsbury's (Doonar, 2004a), the mainstreaming of the market with TV advertising campaigns

and price discounting (Jones et al., 2003), as well as alternative labels linked to ecological issues.

From a review of the existing literature, therefore, in this conceptual paper we suggest that fair

trade can engage with consumers through the areas of green consumption, ethical consumption

and voluntary simplicity and that these conceptualisations are overlapping phenomena.

Furthermore, ethical consumers may be adopting a lifestyle approach to their ethical concerns

through elements of voluntary simplicity or ethical simplicity. This raises a number of issues and

dilemmas for the fair trade movement as fair trade is considered a sub-set of ethical consumerism

(Bird and Hughes, 1997).

Green, ethical & charitable consumer

Ethical Consumers

Semi-ethicals/slavery

Humane consumers

Conserving consumer

Ethical simplifiers

The voluntary simplifier

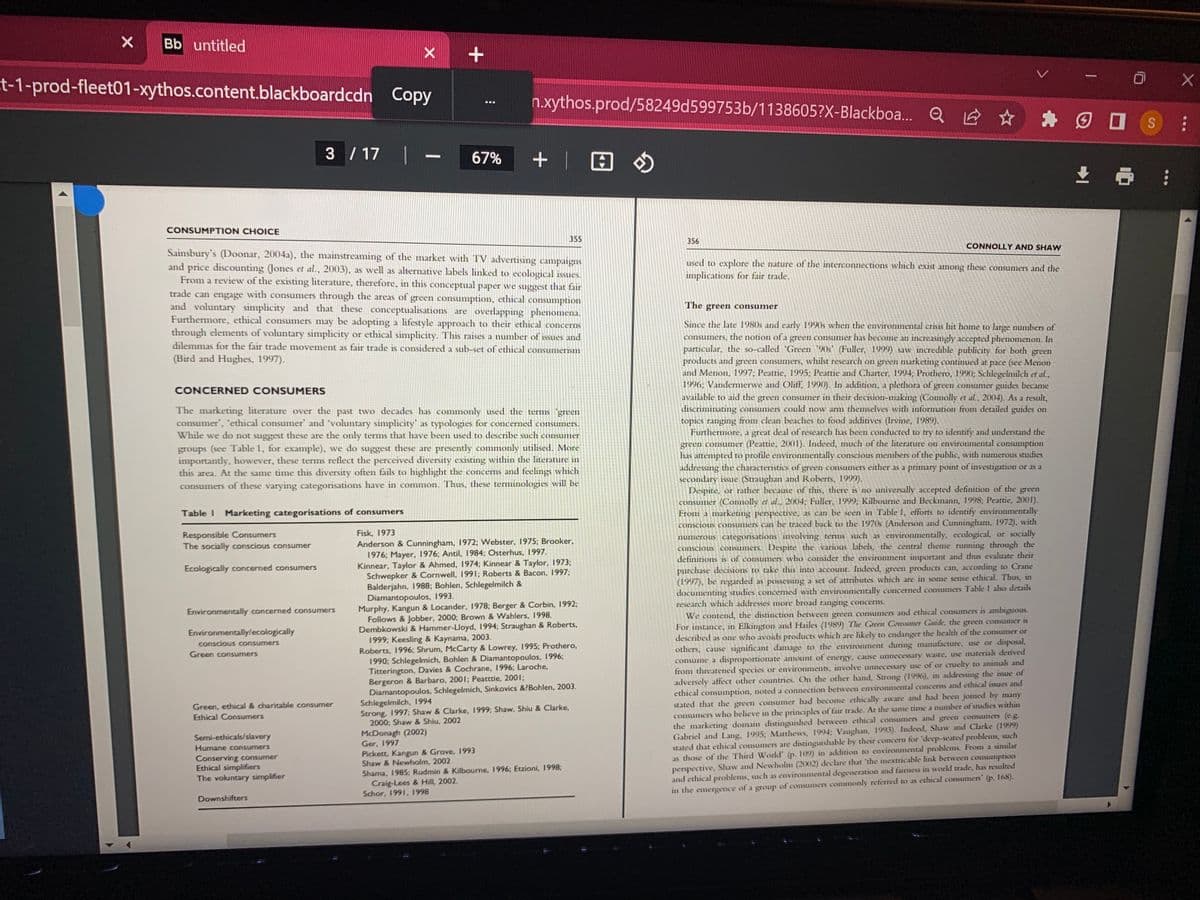

CONCERNED CONSUMERS

The marketing literature over the past two decades has commonly used the terms 'green

consumer', 'ethical consumer' and 'voluntary simplicity' as typologies for concerned consumers.

While we do not suggest these are the only terms that have been used to describe such consumer

groups (see Table 1, for example), we do suggest these are presently commonly utilised. More

importantly, however, these terms reflect the perceived diversity existing within the literature in

this area. At the same time this diversity often fails to highlight the concerns and feelings which

consumers of these varying categorisations have in common. Thus, these terminologies will be

Downshifters

+

Table I Marketing categorisations of consumers

Fisk, 1973

Responsible Consumers

The socially conscious consumer

Ecologically concerned consumers

Anderson & Cunningham, 1972; Webster, 1975; Brooker,

1976; Mayer, 1976; Antil, 1984; Osterhus, 1997.

Kinnear, Taylor & Ahmed, 1974; Kinnear & Taylor, 1973;

Schwepker & Cornwell, 1991; Roberts & Bacon, 1997;

Balderjahn, 1988; Bohlen, Schlegelmilch &

Diamantopoulos, 1993.

***

n.xythos.prod/58249d599753b/1138605?X-Blackboa... Q

67% + | @

355

Ger, 1997

Pickett, Kangun & Grove, 1993

Shaw & Newholm, 2002

Murphy, Kangun & Locander, 1978; Berger & Corbin, 1992;

Follows & Jobber, 2000; Brown & Wahlers, 1998.

Dembkowski & Hammer-Lloyd, 1994; Straughan & Roberts,

1999; Keesling & Kaynama, 2003.

Roberts, 1996; Shrum, McCarty & Lowrey, 1995; Prothero,

1990; Schlegelmich, Bohlen & Diamantopoulos, 1996;

Titterington, Davies & Cochrane, 1996; Laroche,

Bergeron & Barbaro, 2001; Peatttie, 2001;

Diamantopoulos, Schlegelmich, Sinkovics &?Bohlen, 2003.

Schlegelmilch, 1994

Strong, 1997; Shaw & Clarke, 1999; Shaw, Shiu & Clarke,

2000; Shaw & Shiu, 2002

McDonagh (2002)

Shama, 1985; Rudmin & Kilbourne, 1996; Etzioni, 1998;

Craig-Lees & Hill, 2002.

Schor, 1991, 1998

9

356

Q ✰ ✰

CONNOLLY AND SHAW

used to explore the nature of the interconnections which exist among these consumers and the

implications for fair trade.

The green consumer

Since the late 1980s and early 1990s when the environmental crisis hit home to large numbers of

consumers, the notion of a green consumer has become an increasingly accepted phenomenon. In

particular, the so-called 'Green '90s (Fuller, 1999) saw incredible publicity for both green

products and green consumers, whilst research on green marketing continued at pace (see Menon

and Menon, 1997; Peattie, 1995; Peattie and Charter, 1994; Prothero, 1990; Schlegelmilch et al.,

1996; Vandermerwe and Oliff, 1990). In addition, a plethora of green consumer guides became

available to aid the green consumer in their decision-making (Connolly et al., 2004). As a result,

discriminating consumers could now arm themselves with information from detailed guides on

topics ranging from clean beaches to food additives (Irvine, 1989).

Furthermore, a great deal of research has been conducted to try to identify and understand the

green consumer (Peattie, 2001). Indeed, much of the literature on environmental consumption

has attempted to profile environmentally conscious members of the public, with numerous studies

addressing the characteristics of green consumers either as a primary point of investigation or as a

secondary issue (Straughan and Roberts, 1999).

Despite, or rather because of this, there is no universally accepted definition of the green

consumer (Connolly et al., 2004; Fuller, 1999; Kilbourne and Beckmann, 1998; Peattie, 2001).

From a marketing perspective, as can be seen in Table 1, efforts to identify environmentally

conscious consumers can be traced back to the 1970s (Anderson and Cunningham, 1972), with

numerous categorisations involving terms such as environmentally, ecological, or socially

conscious consumers. Despite the various labels, the central theme running through the

definitions is of consumers who consider the environment important and thus evaluate their

purchase decisions to take this into account. Indeed, green products can, according to Crane

(1997), be regarded as possessing a set of attributes which are in some sense ethical. Thus, in

documenting studies concerned with environmentally concerned consumers Table 1 also details

research which addresses more broad ranging concerns.

We contend, the distinction between green consumers and ethical consumers is ambiguous.

For instance, in Elkington and Hailes (1989) The Green Consumer Guide, the green consumer is

described as one who avoids products which are likely to endanger the health of the consumer or

others, cause significant damage to the environment during manufacture, use or disposal,

consume a disproportionate amount of energy, cause unnecessary waste, use materials derived

from threatened species or environments, involve unnecessary use of or cruelty to animals and

adversely affect other countries. On the other hand, Strong (1996), in addressing the issue of

ethical consumption, noted a connection between environmental concerns and ethical issues and

stated that the green consumer had become ethically aware and had been joined by many

consumers who believe in the principles of fair trade. At the same time a number of studies within

the marketing domain distinguished between ethical consumers and green consumers (e.g.

Gabriel and Lang, 1995; Matthews, 1994; Vaughan, 1993). Indeed, Shaw and Clarke (1999)

stated that ethical consumers are distinguishable by their concern for 'deep-seated problems, such

as those of the Third World' (p. 109) in addition to environmental problems. From a similar

perspective, Shaw and Newholm (2002) declare that 'the inextricable link between consumption

and ethical problems, such as environmental degeneration and fairness in world trade, has resulted

in the emergence of a group of consumers commonly referred to as ethical consumers' (p. 168).

↓

S

X

1

Expert Solution

This question has been solved!

Explore an expertly crafted, step-by-step solution for a thorough understanding of key concepts.

Step by step

Solved in 3 steps

Recommended textbooks for you

Principles Of Marketing

Marketing

ISBN:

9780134492513

Author:

Kotler, Philip, Armstrong, Gary (gary M.)

Publisher:

Pearson Higher Education,

Marketing

Marketing

ISBN:

9781259924040

Author:

Roger A. Kerin, Steven W. Hartley

Publisher:

McGraw-Hill Education

Foundations of Business (MindTap Course List)

Marketing

ISBN:

9781337386920

Author:

William M. Pride, Robert J. Hughes, Jack R. Kapoor

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Principles Of Marketing

Marketing

ISBN:

9780134492513

Author:

Kotler, Philip, Armstrong, Gary (gary M.)

Publisher:

Pearson Higher Education,

Marketing

Marketing

ISBN:

9781259924040

Author:

Roger A. Kerin, Steven W. Hartley

Publisher:

McGraw-Hill Education

Foundations of Business (MindTap Course List)

Marketing

ISBN:

9781337386920

Author:

William M. Pride, Robert J. Hughes, Jack R. Kapoor

Publisher:

Cengage Learning

Marketing: An Introduction (13th Edition)

Marketing

ISBN:

9780134149530

Author:

Gary Armstrong, Philip Kotler

Publisher:

PEARSON

Contemporary Marketing

Marketing

ISBN:

9780357033777

Author:

Louis E. Boone, David L. Kurtz

Publisher:

Cengage Learning